The Russian invasion of Ukraine is primarily a human tragedy, but the global economic costs can’t be ignored – and they are piling up. It’s unclear how long the war will go on; the longer it persists, the greater the toll on world economies. As it is, the conflict has put a crimp in economic activity and amplified inflationary pressures that were already stoked by pandemic-related supply shortages. That combination has led some to compare the looming economic environment with the stagflation of the 1970s, a decade that featured many years of sluggish growth, high unemployment, and sharply rising prices.

That said, the U.S. is weathering the geopolitical storm better than its European colleagues, particularly Germany which relies heavily on natural gas imports from Russia. But while oil and gas are more accessible in the U.S., they are also becoming much costlier and fueling the fastest pace of price increases in nearly 40 years. What’s more, things will get worse before they get better. Not only is the pressure from elevated oil prices expected to continue driving inflation higher over the next several months, another wave of Covid-19 is spreading overseas and crippling production, particularly in China where many factories are shut down..

Simply put, snarled supply-chains that were starting to ease late last year are once again getting roiled by the war in Ukraine and new pandemic lockdowns. Shipping costs are soaring, delivery times are lagging, and prices of virtually everything that goes into production are rising faster. Not only are businesses coping with higher costs of supplies, they are also struggling to find workers amidst a scarce pool of job applicants, which is driving up labor costs. Understandably, the Federal Reserve is moving swiftly to an inflation-fighting mode, raising interest rates for the first time since December 2018 and signaling that it will continue on a rate-hiking path through next year. The problem is, the Fed has a poor record of curtailing high inflation without causing a recession. Will this time be different?.

Inflation has been building for over a year, but Americans seem to be finally getting the painful message. With food prices surging, utility bills heating up, rents going through the roof, and prices at the gas pump leaping over $4 a gallon, shoppers are seeing their purchasing power shrink by the day. The consumer price index surged by 7.9 percent in February from a year ago, the fastest in 40 years, and the acceleration is broadening throughout the basket of goods and services that households normally purchase. Excluding volatile food and energy items, the so-called core consumer price index is up by 6.4 percent over the same period, also the strongest in nearly four decades.

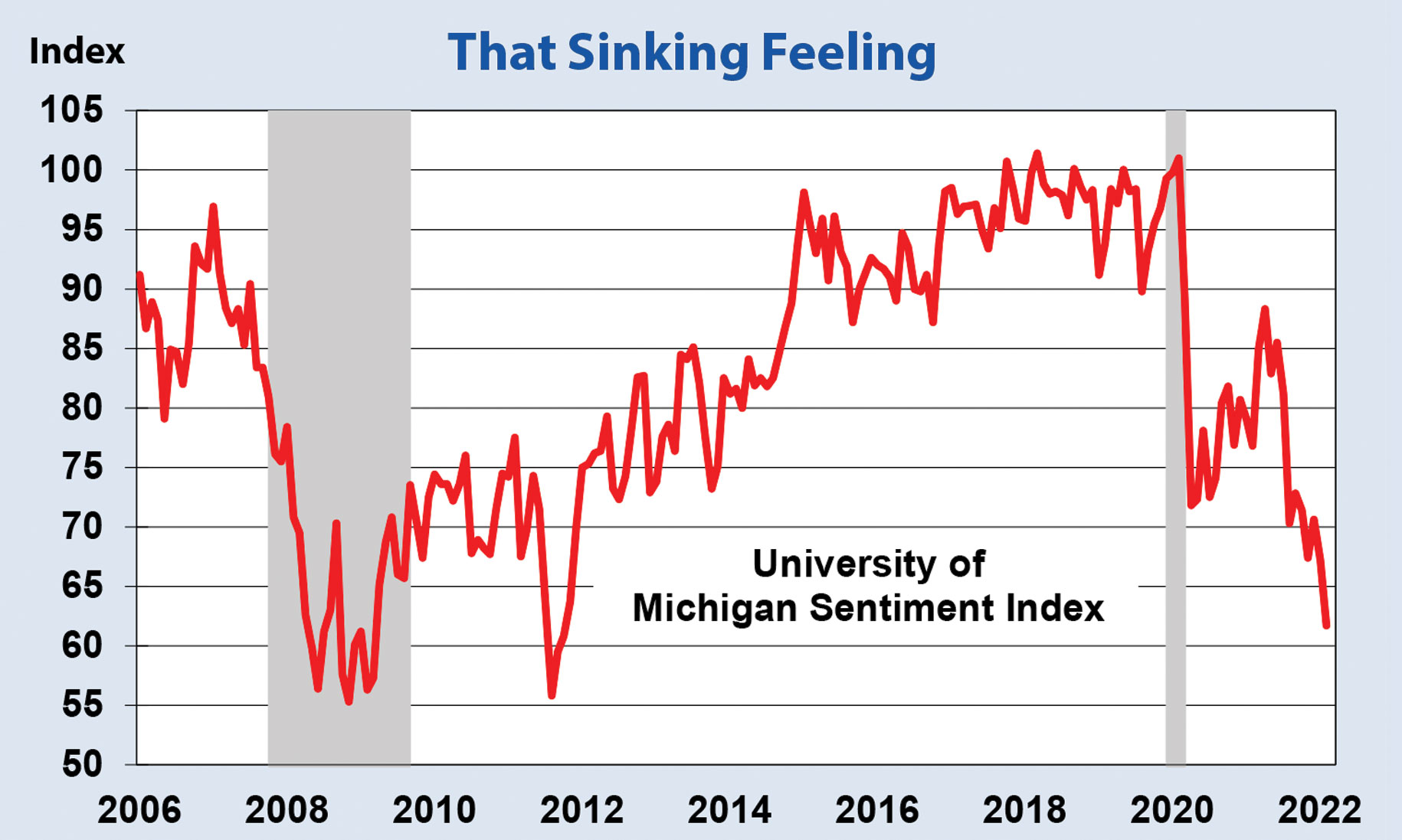

The shock from accelerating price increases is taking a toll on household confidence. An index of consumer sentiment tracked by the University of Michigan, slumped in early March to the lowest level since the summer of 2011, when the economy was struggling to emerge from the deepest recession since the 1930s. Usually when consumer confidence tumbles so badly, it is due to weak employment conditions. In mid-2011, the unemployment rate stood at 9.0 percent, only fitfully retreating from the recession peak of 9.9 percent. With unemployment now at a historically low 3.8 percent, households are saying their chief source of angst is that inflation would continue to erode income gains. Indeed, their expected inflation rate over the next year is the highest since 1981.

That worry together with a robust job market has spurred workers to demand higher wages to keep up with inflation. Their efforts are bearing fruit, as worker pay is also increasing at the fastest clip in decades. Unfortunately, the effort is still falling short, as inflation-adjusted earnings are more than 2 percent lower now than a year ago. The danger is that workers will intensify their efforts to catch up, setting in motion a wage-price spiral that would require a harsh growth-killing response by the Federal Reserve. Not surprisingly, economists as well as traders, see higher odds that the Fed will over-correct and send the economy into a recession.

The First Of Many

In a well-telegraphed move, the Federal Reserve’s policy-setting committee on March 16 voted to increase its short-term rate target a quarter-percentage point from near zero to a range of .25-.50 percent. Given the red-hot inflation environment and the belated recognition by Fed Chairman Jay Powell that rates should have been raised earlier, many believe that a larger increase would have been more appropriate. Indeed, in the weeks prior to the Russian invasion, the financial markets were increasingly pricing in a larger half-point increase at the policy-setting confab.

But the war in Ukraine persuaded the Fed to take a more cautious approach, as the conflict and ensuing sanctions injected the “stag” into the worsening inflation environment. Still, the outbreak of hostilities did not change the Fed’s view that the inflation threat outweighed the potential blow to growth. Hence, while the growth outlook was reduced at the meeting, Fed officials believe the economy has enough muscle to withstand projected rate hikes totaling 1.75 percentage points this year and another three-quarters of percent next, leaving the short-term rate target at 2.75 percent by the end of 2023.

Since the mid-March policy meeting Powell has sounded a more hawkish tone, noting at a recent conference that he would advocate steeper rate hikes if inflation seemed to be getting out of control. Hence a half-point increase is back on the table, either at the next meeting in May or shortly thereafter. Simply put, the Fed is pulling no punches in the inflation fight. With the supply shocks from the war in Ukraine intensifying and getting reinforcement from rising cases of Covid overseas, the odds that it will become more aggressive in tightening policy is growing.

Fed officials think the economy is well equipped to absorb the rate increases without toppling over into a recession. In this regard, it’s important to remember that this inflation spiral is not just a supply-side phenomenon. The massive pandemic-era fiscal stimulus totaling $5 trillion has fueled a torrid increase in demand. And with spending on services curtailed during the pandemic, more of the demand was diverted to goods, which amplified the squeeze on scarce supplies and reinforced pressure on prices.

Importantly, consumers still have fuel in the tank from unspent funds during the pandemic, leaving them with bloated bank accounts that can be used to satisfy pent-up demand. It is estimated that households retain more than $2 trillion in excess savings that can still flow into the spending stream. Those savings together with rising stock and home prices have swollen household balance sheets, making it easier for consumers to accept higher prices. Hence, while the Fed does not have the ability to relieve shortages, it can cool off demand to bring it more in line with supply.

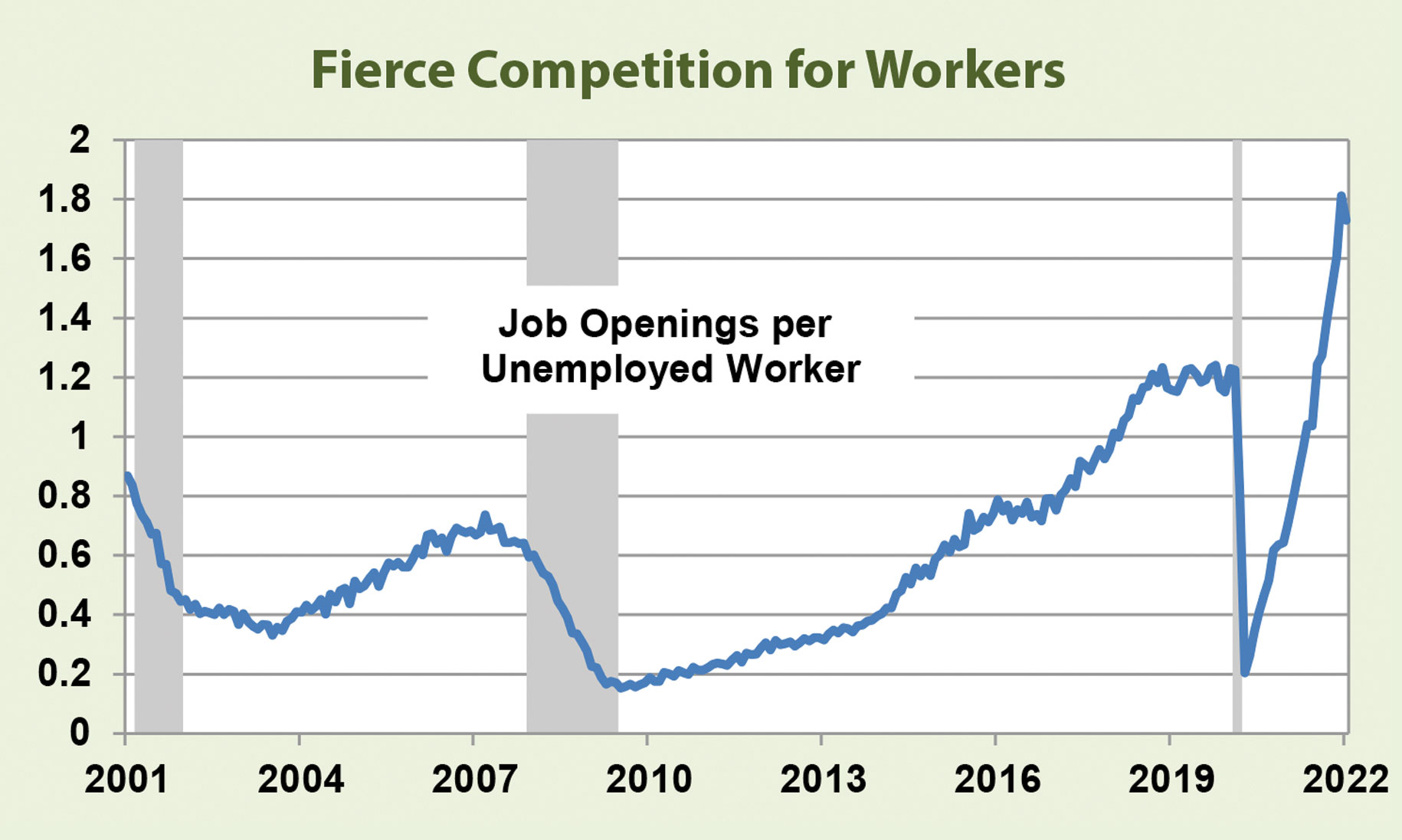

To be sure, balance sheet influences on demand are not permanent. Savings are being drawn down to support consumption and portfolios could be swiftly depleted by a sharp market correction. What the Fed is particularly looking at is the extreme tightness in the labor market, where there are a record 1.7 more job openings than unemployed workers. As chair Powell noted, this is an unhealthy condition that stokes both demand as well as wage inflation, which could become more deeply entrenched the longer it persists. The Fed understandably believes that there is leeway to cool off demand without endangering the expansion, and with momentum still strong, it is probably advisable to start stepping on the brakes sooner rather than later.

The Fed’s ultimate goal is to guide the economy into a soft landing, i.e. slow growth but not kill it while it reins in inflation. But historically things do not end well when the central bank embarks on a rate-hiking campaign. More than 80 percent of the time, it results in a recession. But there have been some successes; Powell likes to point to 1995 as one. From early 1994 to early 1995, the Fed hiked its short-term rate target from 3 to 6 percent, which stifled the rise in inflation without leading to a recession. But the inflation peak then was 3.25 percent, less than half of where it is now. It has never accomplished that feat when inflation topped 5 percent.

That said, there are several things working in favor of a more successful outcome this time. For one, some special forces continue to drive up inflation, which should unwind as conditions normalize. Supply-chain disruptions caused by pandemic-related restrictions will ease as health conditions improve. Likewise, as workers feel more comfortable about returning to offices, the labor supply will expand and curtail wage growth. Consumers, too, are eager to resume normal spending behavior, spending more on services, which will relieve pressure on the prices of goods. Finally, geopolitical tensions should hopefully fade before the end of the year and ease the squeeze driving up oil prices.

It is difficult to measure how much these external shocks to supply have contributed to the inflation surge. The Fed is probably correct that some price pressures will ease on their own as these transitory influences fade. If so, it may not have to move as aggressively to bring inflation down to acceptable levels. But some inflationary influences that were dormant before the onset of the pandemic are likely to stick. It’s doubtful that labor shortages will be resolved anytime soon, thanks to a wave of retirements, reduced immigration, and other factors keeping workers on the sidelines, all of which points to more rapid increases in labor costs than before. And the war in Ukraine is prompting the U.S. to recalibrate trade links for security reasons, with an eye towards producing goods domestically instead of importing them from unreliable nations. That deglobalization trend, should it continue, would increase production costs.

Meanwhile, demand continues to outpace supply and pressure the Fed to sap some of its strength. Although history suggests that it will go too far and send the economy into a recession, that risk is likely higher for 2023 than this year.